Showing posts with label wwii. Show all posts

Showing posts with label wwii. Show all posts

Friday, May 2, 2008

Tuesday, April 22, 2008

Sunday, April 6, 2008

Japs Threaten Hawaii!

7 December 1942 - With American naval forces shattered, the Japanese have cruised through the Pacific on a rampage and are now returning to finish what they started at Pearl Harbor. From bases on the Palmyra Atoll and Johnston Island, the Imperial navy and air forces have been sending sorties time and again to harass Oahu in what appears to be a prelude to invasion. Supplies have already been virtually cut off by Yamamoto's battleships with only the smallest percentage sneaking through.

The nation's nightmares have been realized with the Japs poised to invade American soil. Many point to Midway as the hinge upon which history has taken this dark turn. With American naval power crippled in the battle, no one could stand against Japanese encroachment. Just three weeks after Midway, Dutch Harbor was invaded by Imperial forces and occupied. Through an island hopping campaign, the Japanese seized Guadalcanal virtually unopposed and continued through Espiritu Santo, New Caledonia, Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa. It has only been in the past month that the Japanese turned north in an assault on Canton and Phoenix islands before their invasion of Palmyra. Contact with Australia has been cut off leading to fears for the future of seven million lives.

This comes on the tails of a Nazi invasion in Labrador where German beachheads get stronger everyday. How long before they drive south to our borders?

President Dewey went on record in a speech to Congress: "America is facing her greatest test. The armies of darkness are closing in to smother the last glimmer of democracy in the world. Though we face anihilation, America will survive. We must be brave, be vigilant, and fight not only for ourselves but for the salvation of the world. We cannot, must not fail or else the world itself shall be lost."

President Dewey went on record in a speech to Congress: "America is facing her greatest test. The armies of darkness are closing in to smother the last glimmer of democracy in the world. Though we face anihilation, America will survive. We must be brave, be vigilant, and fight not only for ourselves but for the salvation of the world. We cannot, must not fail or else the world itself shall be lost."

Many wonder what the president will fight with. With rearmament barely two years old, already bottlenecks have stifled lines of production. After the loss at Midway, Congress pressed the Dewey to increase the Army to 100 divisions, robbing expanding industry of manpower and trashing schedules slowing down our military growth. With Hitler on our doorstep, the need for men at the borders is greater than ever yet production has only recently been streamlined and fear runs through the nation that we may be too late to stave off the Devil and his forces.

SOURCE: Courier-Journal

The nation's nightmares have been realized with the Japs poised to invade American soil. Many point to Midway as the hinge upon which history has taken this dark turn. With American naval power crippled in the battle, no one could stand against Japanese encroachment. Just three weeks after Midway, Dutch Harbor was invaded by Imperial forces and occupied. Through an island hopping campaign, the Japanese seized Guadalcanal virtually unopposed and continued through Espiritu Santo, New Caledonia, Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa. It has only been in the past month that the Japanese turned north in an assault on Canton and Phoenix islands before their invasion of Palmyra. Contact with Australia has been cut off leading to fears for the future of seven million lives.

This comes on the tails of a Nazi invasion in Labrador where German beachheads get stronger everyday. How long before they drive south to our borders?

President Dewey went on record in a speech to Congress: "America is facing her greatest test. The armies of darkness are closing in to smother the last glimmer of democracy in the world. Though we face anihilation, America will survive. We must be brave, be vigilant, and fight not only for ourselves but for the salvation of the world. We cannot, must not fail or else the world itself shall be lost."

President Dewey went on record in a speech to Congress: "America is facing her greatest test. The armies of darkness are closing in to smother the last glimmer of democracy in the world. Though we face anihilation, America will survive. We must be brave, be vigilant, and fight not only for ourselves but for the salvation of the world. We cannot, must not fail or else the world itself shall be lost."Many wonder what the president will fight with. With rearmament barely two years old, already bottlenecks have stifled lines of production. After the loss at Midway, Congress pressed the Dewey to increase the Army to 100 divisions, robbing expanding industry of manpower and trashing schedules slowing down our military growth. With Hitler on our doorstep, the need for men at the borders is greater than ever yet production has only recently been streamlined and fear runs through the nation that we may be too late to stave off the Devil and his forces.

SOURCE: Courier-Journal

Labels:

canada,

fiji,

germany,

guadal canal,

hawaii,

hitler,

japan,

labrador,

midway,

nazis,

oahu,

pacific,

pearl harbor,

president,

samoa,

tonga,

united states,

world war ii,

wwii

The Battle of Midway

Prelude to Battle

Yamamoto is uncertain if American forces are taking the bait as he and his naval forces make way for Midway. This would change following Operation K. A night reconnaissance of Pearl Harbor by Kawanishi flying boats from Kwajalein on March 31, 1942 find no American carriers, confirming for the Yamamoto that the American Admiral Chester Nimitz was trying to counter his moves as the Japanese closed on Midway.

The Opening Phase of Midway

Yamamoto set a submarine picket line between Hawaii and Midway. These forces would catch a glimpse of Rear Admiral Raymond Spruance’s carriers moving towards the battle area on April 2 providing early warning of the American approach. Admiral Nagumo responds by having all his escort craft float planes in the air before dawn searching determinedly for the enemy; his air groups would be primed on deck, ready to strike at the first opportunity.

Alerted to America’s readiness to meet him at the outset, Nagumo is poised to unleash his veteran flight leaders to seek out the enemy fleet and destroy it. Not long after dawn on April 4, a contact report comes in: The Americans were sighted-one carrier and escorts. With full concurrence of his air staff, although at extreme range, Nagumo immediately gave the order to launch against the Americans, identified as the Enterprise. Balanced attack groups of Val bombers and Kate torpedo bombers, flown by magnificent air crews, and escorted all the way to their targets by half of Nagumo’s Zero fighters, bear down on Spruance. The Japanese carriers, ready for an American counterattack, spot their fighters on deck, as the armoires prepare Nagumo’s planes for a second strike.

Alerted to America’s readiness to meet him at the outset, Nagumo is poised to unleash his veteran flight leaders to seek out the enemy fleet and destroy it. Not long after dawn on April 4, a contact report comes in: The Americans were sighted-one carrier and escorts. With full concurrence of his air staff, although at extreme range, Nagumo immediately gave the order to launch against the Americans, identified as the Enterprise. Balanced attack groups of Val bombers and Kate torpedo bombers, flown by magnificent air crews, and escorted all the way to their targets by half of Nagumo’s Zero fighters, bear down on Spruance. The Japanese carriers, ready for an American counterattack, spot their fighters on deck, as the armoires prepare Nagumo’s planes for a second strike.A report locating Nagumo’s force from a Midway-based PBY Catalina flying boat comes in just as Task Force 16’s radar picks up what may be incoming Japanese planes. Spruance, himself expecting and seeking contact, launches his own strike at this target. Ray Spruance does this despite the position of the enemy fleet being beyond the round-trip range of many American aircraft; he will attempt to close the distance on their return trip, he tells them, knowing that many will have no chance to make it back. The fighters of TF-16’s Combat Air Patrol, those not sent as escorts on the attack, meet the incoming enemy courageously, but they are knocked aside as Japanese Zeroes engage them aggressively, downing many using their superior maneuverability to screen the Americans from the slower bombers. Few of the attacking bombers are turned aside before they reach the frantically turning American flattops. Within ten minutes, despite the desperate efforts of every antiaircraft gunner in the fleet, torpedoes have rammed home on both beams of the Enterprise. The carrier is ablaze from several large holes on her flight deck. TF-16 is out of action; losses among the attackers are moderate. Heroic attacks and frantic actions still lie ahead.

Even as Ray Spruance transfers his flag from Enterprise while her captain tries desperately to save his ship, the planes of TF-16 are intercepted by a swarm of Japanese fighters as they approach Nagumo’s carrier force. With great courage, most attempt to press home their attacks, but the slow-moving torpedo bombers are slaughtered; the dive-bombers are picked up by more Zeroes, waiting for them on high, which pursue them down their less-than-perfect bombing paths with murderous persistence; all this occurs while the ships of Nagumo’s force are throwing up a curtain of ack-ack, maneuvering skillfully to avoid their attackers. As at Coral Sea, American bombers inflict severe damage on a Japanese carrier, Kaga, but fail to finish her. With their own mother ships devastated, these pilots won’t get a second chance.

Even as Ray Spruance transfers his flag from Enterprise while her captain tries desperately to save his ship, the planes of TF-16 are intercepted by a swarm of Japanese fighters as they approach Nagumo’s carrier force. With great courage, most attempt to press home their attacks, but the slow-moving torpedo bombers are slaughtered; the dive-bombers are picked up by more Zeroes, waiting for them on high, which pursue them down their less-than-perfect bombing paths with murderous persistence; all this occurs while the ships of Nagumo’s force are throwing up a curtain of ack-ack, maneuvering skillfully to avoid their attackers. As at Coral Sea, American bombers inflict severe damage on a Japanese carrier, Kaga, but fail to finish her. With their own mother ships devastated, these pilots won’t get a second chance.The Second Phase

Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher and the Yorktown, core of TF-17, learn of the sighting of Japanese carriers and want to join the action, but he is not yet close enough to participate. His planes ready to go, and making flank speed to the west, he then gets the terrible news from Spruance of his ship’s condition.

Jack Fletcher knows that Vice Admiral “Bull” Halsey would have hurled himself into battle, but he is not “Bull” Halsey, likely to act before considering all the ramifications; nor can he easily abandon Spruance to an unanswered second strike from Nagumo. It is still midmorning. Fletcher believes he has escaped detection and can get a blow in before the enemy finds him, evening up the score. Fletcher makes the decision to sail west, rather than turn back for Pearl, hoping to narrow the range on Nagumo. A scout plane from the Japanese cruiser Tone, on its homeward leg, detects him. Fletcher launches Yorktown’s planes when he gets reports of “enemy carriers,” perhaps to catch Nagumo recovering his aircraft. America’s last hope make their way to Mobile Force’s previous location, but can only find a crippled Kaga limping westward, escorted by two destroyers. Despite searching frantically for Nagumo’s ships, which have made a sharp turn to the north to recover, they can find no fresh targets. The flight groups from Yorktown overwhelm the damaged Japanese carrier, dispatching her and one of her escorts in frustration.

While the American aircrews are pounding Kaga, Fletcher’s flagship becomes the target of a ferocious attack in turn. Nagumo’s other three carriers, having recovered their planes at the prearranged rendezvous to the north, launch their second strike against Yorktown, stalked by several floatplanes; she is a smoldering hulk by nightfall. Fletcher’s planes are lost when they return to the site, though some of the aircrews who can make it back to all that remains of TF-17 are able to splash nearby. In a single day, Yorktown has been wrecked and scuttled by the same crew who had seen her saved just a few days before, while Enterprise, trying to make it home, the fires put out but her flight deck ruined, becomes an easy target for one of Japan’s submarines, just as Lexington had been at Coral Sea; torpedoed, she sinks near dawn the next day, the fifth of April. The Japanese navy’s surface units close in for night action to pick off any damaged vessels and American survivors of lost ships and ditched planes bobbing about in the water. Over the next few days, Japanese destroyers find many survivors, Americans and Japanese, though there is little joy for the prisoners, who find their rescuers interested only in what information they can provide about the defenses of Midway and Hawaii before they are killed. The loss has stripped America’s naval air corps of its core of fine pilots and experienced aircrews, while possession of this “ocean battlefield” means many downed Japanese airmen will fly again.

While the American aircrews are pounding Kaga, Fletcher’s flagship becomes the target of a ferocious attack in turn. Nagumo’s other three carriers, having recovered their planes at the prearranged rendezvous to the north, launch their second strike against Yorktown, stalked by several floatplanes; she is a smoldering hulk by nightfall. Fletcher’s planes are lost when they return to the site, though some of the aircrews who can make it back to all that remains of TF-17 are able to splash nearby. In a single day, Yorktown has been wrecked and scuttled by the same crew who had seen her saved just a few days before, while Enterprise, trying to make it home, the fires put out but her flight deck ruined, becomes an easy target for one of Japan’s submarines, just as Lexington had been at Coral Sea; torpedoed, she sinks near dawn the next day, the fifth of April. The Japanese navy’s surface units close in for night action to pick off any damaged vessels and American survivors of lost ships and ditched planes bobbing about in the water. Over the next few days, Japanese destroyers find many survivors, Americans and Japanese, though there is little joy for the prisoners, who find their rescuers interested only in what information they can provide about the defenses of Midway and Hawaii before they are killed. The loss has stripped America’s naval air corps of its core of fine pilots and experienced aircrews, while possession of this “ocean battlefield” means many downed Japanese airmen will fly again.Midway Island in range, Nagumo’s planes from the Mobile Fleet reduce the island’s airbase to rubble, its aircraft burned or expended in futile efforts to sink fast ships at sea. Midway is then pummeled by the big guns of the Support Group’s cruisers and then even the Main Force battleships under Admiral Yamamoto himself, hurling 16 and 18.1 inch shells against coral. The American garrison, even reinforced as it is, can hardly resist for long unsupported, once Japanese troops are ashore. It proves a bloody affair and a formidable warning for Japan of the dangers inherent in making opposed landings against the U.S. Marines in base-defense mode; the garrison adds “Midway” to the name of “The Alamo,” “Wake,” and “Bataan” in America’s hagiography of last stands.

Admiral Chester Nimitz finds himself with just a single carrier in the Pacific: Saratoga, just in from San Diego. Halsey wants to steam off directly toward the enemy, “catch ‘em gloating,” as he puts it, but Nimitz is aware that the strategic defense he had planned has been ruined by his own impetuosity. He had gone on a hunch, but it was a very thin strand that had held it all together. There never seemed to be any consideration of whether the Japanese might have guessed his plans. Most of the fleet had been risked and now it was gone. How could expert strategic intelligence have produced such a catastrophic defeat? How could he have guessed right and still be defeated?

SOURCE: Dietrich, Robert Point Luck: The American Tragedy of Midway

Labels:

alternate history,

fletcher,

halsey,

midway,

pacific theater,

spruance,

wwii,

yamamoto,

yorktown

Saturday, April 5, 2008

The Battle of Midway: Planning Stage

The Battle of Midway was a major naval battle in the Pacific War. It took place from April 4, 1942 to April 7, 1942, approximately one month after the Battle of the Coral Sea, five months after the Japanese capture of Wake Island, and exactly six months to the day after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor.

The Japanese plan of attack was to lure America's remaining carriers into a trap and sink them. The Japanese also intended to occupy Midway Atoll to extend Japan's defensive perimeter farther from its home islands. This operation was preparatory for further attacks against Fiji and Samoa, and Hawaii.

The Midway operation was aimed at the elimination of the United States as a strategic Pacific power, thereby giving Japan a free hand in establishing its Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. It was also hoped another defeat would force the U.S. to negotiate an end to the Pacific War with conditions favorable for Japan.

Japan had been highly successful in rapidly securing its initial war goals, including the takeover of the Philippines, capture of Malaya and Singapore, and securing vital resource areas in Java, Borneo, and other islands of the Dutch East Indies. As such, preliminary planning for a second phase of operations commenced as early as November 1941. However, because of strategic differences between the Imperial Army and Imperial Navy, as well as infighting between the Navy's GHQ and Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s Combined Fleet, the formulation of effective strategy was hampered, and the follow-up strategy was not finalized until February 1942. Admiral Yamamoto succeeded in winning a bureaucratic struggle placing his operational concept — further operations in the Central Pacific — ahead of other contending plans. These included operations either directly or indirectly aimed at Australia and into the Indian Ocean. In the end, Yamamoto's barely-veiled threat to resign unless he got his way succeeded in carrying his agenda forward.

Yamamoto's primary strategic concern was the elimination of America's remaining carrier forces. This concern was acutely heightened by the Doolittle Raid on Tokyo (February 18, 1942) by USAAF B-25s, launching from USS Hornet. The raid, while militarily insignificant, was a severe psychological shock to the Japanese and proved the existence of a gap in the defenses around the Japanese home islands. Sinking America's aircraft carriers and seizing Midway, the only strategic island besides Hawaii in the East Pacific, was seen as the only means of nullifying this threat. Yamamoto reasoned an operation against the main carrier base at Pearl Harbor would induce the U.S. forces to fight. However, given the strength of American land-based air-power on Hawaii, he judged the powerful American base could not be attacked directly. Instead, he selected Midway, at the extreme northwest end of the Hawaiian Island chain, some 1,300 miles (2,100 km) from Oahu. Midway was not especially important in the larger scheme of Japan's intentions; however, the Japanese felt the Americans would consider Midway a vital outpost of Pearl Harbor and would therefore strongly defend it.

Yamamoto's Plan

Typical of Japanese naval planning during the Second World War, Yamamoto's battle plan was quite complex. Additionally, his designs were predicated on optimistic intelligence information suggesting USS Enterprise and USS Hornet, forming Task Force 16, were the only carriers available to the U.S. Pacific Fleet at the time. USS Lexington had been sunk and USS Yorktown severely damaged (and IJN believed her sunk) at the Battle of the Coral Sea just a month earlier. Likewise, the Japanese were aware USS Saratoga was undergoing repairs on the West Coast after taking torpedo damage from a submarine. As such, the Japanese believed they faced at most two American fleet carriers at the point of contact.

More important, however, was Yamamoto's belief the Americans had been demoralized by their frequent defeats during the preceding six months. Yamamoto felt deception would be required to lure the U.S. Fleet into a fatally compromising situation. To this end, he dispersed his forces so their full extent (particularly his battleships) would be unlikely to be discovered by the Americans prior to battle. However, his emphasis on dispersal meant none of his formations were mutually supporting.

Critically, Yamamoto's supporting battleships and cruisers would trail Vice-Admiral Chuichi Nagumo's carrier striking force by several hundred miles. Japan's heavy surface forces were intended to destroy whatever part of the U.S. Fleet might come to Midway's relief, once Nagumo's carriers had weakened them sufficiently for a daylight gun duel to be fought; this was typical of the battle doctrine of most major navies.

Also, Japanese operations aimed at the Aleutian Islands (Operation AL). However, a one-day delay in the sailing of Nagumo's task force had the effect of initiating Operation AL a day before its counterpart.

Prelude to Battle

U.S. Forces

In order to do battle with an enemy force anticipated to be composed of 4 or 5 carriers, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas, needed every available U.S. flight deck. He already had Vice Admiral William Halsey's two-carrier (Enterprise and Hornet) task force at hand; Halsey was stricken with psoriasis and was replaced by Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance (Halsey's escort commander). Nimitz also hurriedly called back Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher's task force from the South West Pacific Area. He reached Pearl Harbor just in time to provision and sail. Saratoga was still under repair, and Yorktown had been severely damaged at the Battle of the Coral Sea, but Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard worked around the clock to patch up the carrier. Though several months of repairs at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard was estimated for Yorktown, 72 hours was enough to restore her to a battle-worthy (if still not structurally ideal) state. Her flight deck was patched, whole sections of internal frames were cut out and replaced, and several new squadrons (drawn from the Saratoga) were put aboard. Nimitz showed disregard for established procedure in getting his third and last available carrier ready for battle — repairs continued even as Yorktown sortied, with work crews from the repair ship USS Vestal—herself damaged in the attack on Pearl Harbor six months earlier—still aboard. Just three days after putting into drydock at Pearl Harbor, Yorktown was again under steam.

Japanese Forces

Meanwhile, as a result of their participation in the Battle of the Coral Sea, the Japanese carrier Zuikaku was in port in Kure, awaiting a replacement air group. The heavily damaged Shōkaku was under repair from three bomb hits suffered at Coral Sea, and required months in drydock. Despite the likely availability of sufficient aircraft between the two ships to re-equip Zuikaku with a composite air group, the Japanese made no serious attempt to get her into the forthcoming battle. Consequently, instead of bringing five intact fleet carriers into battle, Admiral Nagumo would only have four: Kaga, with Akagi, forming Division 1; Hiryū and Sōryū, as the 2nd Division. At least part of this was a product of fatigue; Japanese carriers had been constantly on operations since October 7, 1941, including pinprick raids on Darwin and Colombo.

Japanese strategic scouting arrangements prior to the battle also fell into disarray. A picket line of Japanese submarines was late getting into position (partly because of Yamamoto's haste), which let the American carriers proceed to their assembly point northeast of Midway (known as "Point Luck") without being detected. A second attempt to use four-engine reconnaissance flying boats to scout Pearl Harbor prior to the battle (and thereby detect the absence or presence of the American carriers), known as "Operation K", was also thwarted when Japanese submarines assigned to refuel the search aircraft discovered the intended refueling point — a hitherto deserted bay off French Frigate Shoals — was occupied by American warships (because the Japanese had carried out an identical mission in January). Thus, Japan was deprived of any knowledge concerning the movements of the American carriers immediately before the battle.

Japanese radio intercepts also noticed an increase in both American submarine activity and U.S. message traffic. This information was in Yamamoto's hands prior to the battle. However, Japanese plans were not changed in reaction to this; Yamamoto, at sea in Yamato, did not dare inform Nagumo without exposing his position, and presumed (incorrectly) Nagumo had received the same signal from Tokyo.

Intelligence and Counterintellgience

Admiral Nimitz had one priceless asset: American and British cryptanalysts had broken the JN-25 code. Commander Joseph J. Rochefort and his team at HYPO were able to confirm Midway as the target of the impending Japanese strike and to determine the date of the attack as either 4 or 5 April (as opposed to mid-April, maintained by Washington).

This was not accomplished without ingenuity on the Navy's part. They had only cracked 10% of the Japanese code and had to rely heavily on hunches and guesses to determine Japanese plans. When knowledge of a Japanese offensive aimed at some point in the Pacific became known, AF, the Naval cryptographers nailed down a potential list and began openly broadcasting the status of these "candidates" to see the Japanese response. For Midway, a broadcast of the island "being short of water" was sent over the airwaves. Midway was later confirmed as point AF when the Japanese broadcast that "AF was short of water".

This "intelligence" had not been discovered by sheer American and British skill and luck. A Japanese sailor, Ryu Hayabusa, was responsible for transcribing American radio messages the day the broadcast of Midway's water problem was received. After copying the message down, something gnawed at him. The content of the message and the way it was received did not quite fit. Hayabusa turned to his superior and asked, "Why are they broadcasting this message in the clear? Don't they care if we know that Midway is running short of water?" His superior would pass on Ryu's doubts. This led to questions being asked by cryptographers and cipher specialists in Tokyo over whether the Americans had broken their code. One specialist reasoned that perhaps the Americans were reading their messages and using a gambit to link potential objectives and cipher designations, in this case the code word for Midway. This raised a red flag at Imperial General Headquarters Tokyo.

Many of the Imperial Staff argued that Yamamoto's planned invasion should be cancelled, but Yamamoto would not hear of it. If the Americans had, in fact, gotten wind of their operations, all the better. Knowing the objective, the Americans would not allow Midway to fall into Japanese hands without a sizable fight. This was his opportunity to finally draw the Americans into the decisive battle he'd been hoping for.

On March 19, 1942, the Japanese radioed that "AF was running short of water." The Japanese were going to lure the Americans in.

SOURCE: Dietrich, Robert Point Luck: The American Tragedy of Midway

The Japanese plan of attack was to lure America's remaining carriers into a trap and sink them. The Japanese also intended to occupy Midway Atoll to extend Japan's defensive perimeter farther from its home islands. This operation was preparatory for further attacks against Fiji and Samoa, and Hawaii.

The Midway operation was aimed at the elimination of the United States as a strategic Pacific power, thereby giving Japan a free hand in establishing its Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. It was also hoped another defeat would force the U.S. to negotiate an end to the Pacific War with conditions favorable for Japan.

Japan had been highly successful in rapidly securing its initial war goals, including the takeover of the Philippines, capture of Malaya and Singapore, and securing vital resource areas in Java, Borneo, and other islands of the Dutch East Indies. As such, preliminary planning for a second phase of operations commenced as early as November 1941. However, because of strategic differences between the Imperial Army and Imperial Navy, as well as infighting between the Navy's GHQ and Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s Combined Fleet, the formulation of effective strategy was hampered, and the follow-up strategy was not finalized until February 1942. Admiral Yamamoto succeeded in winning a bureaucratic struggle placing his operational concept — further operations in the Central Pacific — ahead of other contending plans. These included operations either directly or indirectly aimed at Australia and into the Indian Ocean. In the end, Yamamoto's barely-veiled threat to resign unless he got his way succeeded in carrying his agenda forward.

Yamamoto's primary strategic concern was the elimination of America's remaining carrier forces. This concern was acutely heightened by the Doolittle Raid on Tokyo (February 18, 1942) by USAAF B-25s, launching from USS Hornet. The raid, while militarily insignificant, was a severe psychological shock to the Japanese and proved the existence of a gap in the defenses around the Japanese home islands. Sinking America's aircraft carriers and seizing Midway, the only strategic island besides Hawaii in the East Pacific, was seen as the only means of nullifying this threat. Yamamoto reasoned an operation against the main carrier base at Pearl Harbor would induce the U.S. forces to fight. However, given the strength of American land-based air-power on Hawaii, he judged the powerful American base could not be attacked directly. Instead, he selected Midway, at the extreme northwest end of the Hawaiian Island chain, some 1,300 miles (2,100 km) from Oahu. Midway was not especially important in the larger scheme of Japan's intentions; however, the Japanese felt the Americans would consider Midway a vital outpost of Pearl Harbor and would therefore strongly defend it.

Yamamoto's Plan

Typical of Japanese naval planning during the Second World War, Yamamoto's battle plan was quite complex. Additionally, his designs were predicated on optimistic intelligence information suggesting USS Enterprise and USS Hornet, forming Task Force 16, were the only carriers available to the U.S. Pacific Fleet at the time. USS Lexington had been sunk and USS Yorktown severely damaged (and IJN believed her sunk) at the Battle of the Coral Sea just a month earlier. Likewise, the Japanese were aware USS Saratoga was undergoing repairs on the West Coast after taking torpedo damage from a submarine. As such, the Japanese believed they faced at most two American fleet carriers at the point of contact.

More important, however, was Yamamoto's belief the Americans had been demoralized by their frequent defeats during the preceding six months. Yamamoto felt deception would be required to lure the U.S. Fleet into a fatally compromising situation. To this end, he dispersed his forces so their full extent (particularly his battleships) would be unlikely to be discovered by the Americans prior to battle. However, his emphasis on dispersal meant none of his formations were mutually supporting.

Critically, Yamamoto's supporting battleships and cruisers would trail Vice-Admiral Chuichi Nagumo's carrier striking force by several hundred miles. Japan's heavy surface forces were intended to destroy whatever part of the U.S. Fleet might come to Midway's relief, once Nagumo's carriers had weakened them sufficiently for a daylight gun duel to be fought; this was typical of the battle doctrine of most major navies.

Also, Japanese operations aimed at the Aleutian Islands (Operation AL). However, a one-day delay in the sailing of Nagumo's task force had the effect of initiating Operation AL a day before its counterpart.

Prelude to Battle

U.S. Forces

In order to do battle with an enemy force anticipated to be composed of 4 or 5 carriers, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas, needed every available U.S. flight deck. He already had Vice Admiral William Halsey's two-carrier (Enterprise and Hornet) task force at hand; Halsey was stricken with psoriasis and was replaced by Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance (Halsey's escort commander). Nimitz also hurriedly called back Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher's task force from the South West Pacific Area. He reached Pearl Harbor just in time to provision and sail. Saratoga was still under repair, and Yorktown had been severely damaged at the Battle of the Coral Sea, but Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard worked around the clock to patch up the carrier. Though several months of repairs at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard was estimated for Yorktown, 72 hours was enough to restore her to a battle-worthy (if still not structurally ideal) state. Her flight deck was patched, whole sections of internal frames were cut out and replaced, and several new squadrons (drawn from the Saratoga) were put aboard. Nimitz showed disregard for established procedure in getting his third and last available carrier ready for battle — repairs continued even as Yorktown sortied, with work crews from the repair ship USS Vestal—herself damaged in the attack on Pearl Harbor six months earlier—still aboard. Just three days after putting into drydock at Pearl Harbor, Yorktown was again under steam.

Japanese Forces

Meanwhile, as a result of their participation in the Battle of the Coral Sea, the Japanese carrier Zuikaku was in port in Kure, awaiting a replacement air group. The heavily damaged Shōkaku was under repair from three bomb hits suffered at Coral Sea, and required months in drydock. Despite the likely availability of sufficient aircraft between the two ships to re-equip Zuikaku with a composite air group, the Japanese made no serious attempt to get her into the forthcoming battle. Consequently, instead of bringing five intact fleet carriers into battle, Admiral Nagumo would only have four: Kaga, with Akagi, forming Division 1; Hiryū and Sōryū, as the 2nd Division. At least part of this was a product of fatigue; Japanese carriers had been constantly on operations since October 7, 1941, including pinprick raids on Darwin and Colombo.

Japanese strategic scouting arrangements prior to the battle also fell into disarray. A picket line of Japanese submarines was late getting into position (partly because of Yamamoto's haste), which let the American carriers proceed to their assembly point northeast of Midway (known as "Point Luck") without being detected. A second attempt to use four-engine reconnaissance flying boats to scout Pearl Harbor prior to the battle (and thereby detect the absence or presence of the American carriers), known as "Operation K", was also thwarted when Japanese submarines assigned to refuel the search aircraft discovered the intended refueling point — a hitherto deserted bay off French Frigate Shoals — was occupied by American warships (because the Japanese had carried out an identical mission in January). Thus, Japan was deprived of any knowledge concerning the movements of the American carriers immediately before the battle.

Japanese radio intercepts also noticed an increase in both American submarine activity and U.S. message traffic. This information was in Yamamoto's hands prior to the battle. However, Japanese plans were not changed in reaction to this; Yamamoto, at sea in Yamato, did not dare inform Nagumo without exposing his position, and presumed (incorrectly) Nagumo had received the same signal from Tokyo.

Intelligence and Counterintellgience

Admiral Nimitz had one priceless asset: American and British cryptanalysts had broken the JN-25 code. Commander Joseph J. Rochefort and his team at HYPO were able to confirm Midway as the target of the impending Japanese strike and to determine the date of the attack as either 4 or 5 April (as opposed to mid-April, maintained by Washington).

This was not accomplished without ingenuity on the Navy's part. They had only cracked 10% of the Japanese code and had to rely heavily on hunches and guesses to determine Japanese plans. When knowledge of a Japanese offensive aimed at some point in the Pacific became known, AF, the Naval cryptographers nailed down a potential list and began openly broadcasting the status of these "candidates" to see the Japanese response. For Midway, a broadcast of the island "being short of water" was sent over the airwaves. Midway was later confirmed as point AF when the Japanese broadcast that "AF was short of water".

This "intelligence" had not been discovered by sheer American and British skill and luck. A Japanese sailor, Ryu Hayabusa, was responsible for transcribing American radio messages the day the broadcast of Midway's water problem was received. After copying the message down, something gnawed at him. The content of the message and the way it was received did not quite fit. Hayabusa turned to his superior and asked, "Why are they broadcasting this message in the clear? Don't they care if we know that Midway is running short of water?" His superior would pass on Ryu's doubts. This led to questions being asked by cryptographers and cipher specialists in Tokyo over whether the Americans had broken their code. One specialist reasoned that perhaps the Americans were reading their messages and using a gambit to link potential objectives and cipher designations, in this case the code word for Midway. This raised a red flag at Imperial General Headquarters Tokyo.

Many of the Imperial Staff argued that Yamamoto's planned invasion should be cancelled, but Yamamoto would not hear of it. If the Americans had, in fact, gotten wind of their operations, all the better. Knowing the objective, the Americans would not allow Midway to fall into Japanese hands without a sizable fight. This was his opportunity to finally draw the Americans into the decisive battle he'd been hoping for.

On March 19, 1942, the Japanese radioed that "AF was running short of water." The Japanese were going to lure the Americans in.

SOURCE: Dietrich, Robert Point Luck: The American Tragedy of Midway

Thursday, April 3, 2008

Annexations Mark Fuhrer's Birthday (Excerpt)

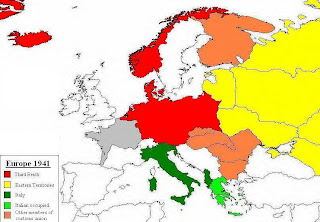

20 April 1941 - To mark the Fuhrer's 52nd birthday, Norway, Denmark, Holland, and Flemish Belgium will be annexed to the Reich. Grand pomp and ceremony will be held in the Reichstag to celebrate the expansion of the Reich and the ongoing leadership of our Fuhrer.

Already there is much to applaud. With the end of the second Great War and the collapse of the Soviet Union, peace and prosperity have spread throughout Germany. The demobilization of the Wermacht has allowed sons, brothers, and fathers to return to their families while the newly acquired eastern frontier provides room for future generations. The economy thrives and Germany stands leader of all Europe.

SOURCE: Völkischer Beobachter

Already there is much to applaud. With the end of the second Great War and the collapse of the Soviet Union, peace and prosperity have spread throughout Germany. The demobilization of the Wermacht has allowed sons, brothers, and fathers to return to their families while the newly acquired eastern frontier provides room for future generations. The economy thrives and Germany stands leader of all Europe.

SOURCE: Völkischer Beobachter

Labels:

1941,

alternate history,

germany,

hitler,

nazis,

reichstag,

third reich,

world war ii,

wwii

Sunday, March 30, 2008

Wednesday, March 26, 2008

Monday, March 24, 2008

Operation WOTAN: August 7, 1940 -September 24, 1940

Operation WOTAN Begins

Operation WOTAN BeginsOn X-Day Panzer Group 1 was in action on the southern side of the encircling ring around Kiev; Guderian’s Group 2, leaving XXXXVIII Corps at Priluki, had disengaged from the encirclement’s northern side and had concentrated around Glukhov; while Panzer Groups 3 and 4 were still deeply committed to the battles at Briansk and Vyasma. The long advance to battle which they would have to undertake meant that they would enter late into the second stage of WOTAN. Guderian, impatient to march, decided that if the other groups were not in position by X-Day then he would open the operation without them. His formations moved forward, and at dawn on the misty morning of 9 August, the order came: “Panzer marsch.” Guderian named as his Group’s first objective the road and rail communications center of Orel. General Geyr von Schweppenburg’s XXIV Panzer Corps, with 3rd and 4th Panzer Divisions in the line, advanced up the Orel Road, while Lemelsen’s XXXXVII Panzer Corps, fielding 17th and 18th Panzer Divisions, flooded across the lightly undulating terrain to the north of the highway.

Guderian’s soldiers were confident. On the eve of the offensive Heini Gross, serving in one of the panzer battalions of 4th Division, wrote “Last evening the Corps Commander visited us. There were several speeches and then we all sang the ‘Panzerlied.’ Very, very moving. Tomorrow at 05:30 we open the attack which will win the war.”

Guderian’s first blows smashed the left wing of Yeremenko’s Front and within a day had crushed Thirteenth Red Army. Soviet counterattacks launched by two Cavalry Divisions and two Tank Brigades were flung back in disarray by 4th Panzer Division. Through the gap which had been created XXIV Corps struck for Sensk, captured it and drove on towards Orel while XXXXVII Corps swung northeastwards for Karachev and Briansk. To the north of Guderian, von Weichs’ Second Infantry Army brought about the collapse of Yeremenko’s right wing when it split asunder the Forty-third and Fiftieth Red Armies. Within two days Panzer Group 2 had driven 130km through the Soviet battle line against minimal opposition. A breach had been made between Orel and Kursk and Kesselring directed the other Panzer Groups to reach and pass through “Guderian’s Gap,” in order to begin the exploitation phase of WOTAN. That order drove Kleist’s Panzer Group 1 northwards from the Kiev ring and was to send Groups 3 and 4 southwards once the main part of their forces had been withdrawn from the Vyasma encirclement battles.

On 11 August, the first air drop was made to Guderian’s Group. Friedrich Huber in a Flak battery recalled, “Fighter aircraft circled above us to drive off any Russian machines. Then the Ju-52s flew in, approaching from the west at a great height, descended lower and circled. They roared low above our heads, the yellow identification stripe [carried by aircraft on the Eastern Front] glowing in the sunlight. A cascade of boxes and the first flight climbed, circled and flew back westwards. In less than ten minutes forty Ju’s had supplied us. Another flight of forty came in, delivered and flew off to be followed by a third wave. This is an idea of the Fuhrer, of course. Simple and effective, swift and efficient…”

Stavka’s reaction to the 2nd Panzer Group attack was sluggish and the weak tank attacks against XXIV Corps were repulsed with heavy loss. Guderian’s Group gained ground at such pace that it was confidently believed the hard crust of the Soviet defense must have been cracked. But it had not. Supreme Stavka ordered that Tula, on the southern approaches to Moscow, was to be held to the last, and the fanatical Soviet defense of the area between the city and Mtsensk brought the first check to 2nd Panzer Group’s drive.

Kesselring, who had been elated at the fall of Orel on 12 August, intended to capitalize on that success by changing WOTAN’s thrust line. Hitler had ordered this to the northeasterly: Dankov-Kasimov-Gorki. That original direction Kesselring now changed so that it marched northwards from Orel, via Mtsensk and Tula, to attack Moscow from due south.

Guderian’s Panzer Group Checked at Mtsensk

It was Colonel Katukov’s armor positioned south of Mtsensk that checked Guderian. A post-battle report, by the staff of XXIV Panzer Corps described the first two days of battle:

“The unit confronting us on Tula road was 4th Tank Brigade. They fought with a terrifying ferocity, even their crews assaulting us with small arms once their tanks had been destroyed. We overcame such resistance by calling Stuka strikes and by setting up lines of our 88mm anti-aircraft guns and employing these in a ground role.”

Kesselring’s disobedience of Hitler’s order forbidding Panzer Army Group to become involved in pitched battles had resulted in Guderian’s drive faltering. To retrieve the situation OKH moved Second Infantry Army from 2nd Panzer Group’s left flank to its right and gave the infantry force the task of capturing Tula. Guderian’s Group, relieved on 16 August, then raced for its next objective, Yelets to the northwest of Voronezh and some 160km distant. Its advance was still unsupported. The other Panzer Groups had still not yet reached the breached area.

Hitler had correctly forecast that Stavka’s slow reaction to WOTAN would allow the Panzer Army Group to gain ground swiftly and Guderian met little organized opposition en route to Yelets. It was principally ill-trained local garrisons reinforced by untrained factory militias who came out to contest the German advance. Lacking adequate training they were slaughtered.

The crossing of the Olym river might have delayed Guderian more than the Russian enemy, but Hitler’s insistence upon extra pioneer units to accompany the Panzer Groups had proved him right and six tank-bearing bridges were erected in a single day. On 20 August Guderian’s reconnaissance detachments entered the outskirts of Yelets and quickly captured the town. The leading elements pressed on: the next water barrier was the mighty Don where Panzer Group 2 could expect to meet serious resistance unless the river could be “bounced”. For the Don crossing Guderian demanded the strongest Stuka support. His Divisions moved towards the river ready to cross on 23 August.

At dawn on that day the Stukas, the Black Hussars of the air, flew over the battle area and systematically destroyed everything which moved on the Don’s eastern bank. Yelets came within the defense zone of Voronezh and was ringed by deep field fortifications and extensive mine fields. “We attacked under cover of a smoke screen across a vast, flat and open piece of ground towards the Don,” explained Hauptmann Heinrich Auer. “On our sector the bluffs were over 100 meters high but upstream where they were almost at water level the Pioneers constructed bridges. We motorized infantry crossed in assault boats, then scaled the bluffs to storm the bunkers and trenches. The Stukas had bombed the Ivans so thoroughly that they were ready to surrender…

“It is not true that the crossing was easy. It was not but at its end we had broken the Don river line. Our panzers crossed the first bridge at about 1400hrs and came up to support us. Together we fought all that night and most of the next day. By the afternoon of the 24th we had reached the confluence of the Don and the Sosna, to the west of Lipetsk, and dug in there. The panzers left us at that point and wheeled north towards Lebyedan…”

Kleist Moves North

On 12 August, Kesselring ordered Kleist’s Panzer Group 1 to advance on a broad front, “…left flank on Kursk and the right on Gubkin…to drive northeastwards to gain touch with Guderian at Yelets.” Once he was in position on Guderian’s right Kleist was next to strike southeastwards and capture Voronezh before changing direction again, northwards to create the western wall of the salient.

Kleist’s Group, like Guderian’s, had not had to cover such vast distances as either Hoth or Hoepner but its advance had been slowed by deep mud and by a surprising fuel famine. A mechanical defect in Elekta, the ground identification signal apparatus, caused the Ju transports to overfly Kleist and to airdrop their cargoes over Guderian. It took nearly four days to identify and to rectify that fault, by which time Kleist was so short of fuel that his Group’s advance was reduced to that of a single Panzer Company. Drastic shortages call for radical action and Kesselring’s solution was direct. Every Heinkel III in VIII Air Corps was loaded with fuel and ammunition and the massed squadrons touched down on the Kursk uplands at Swoboda where Kleist’s Group had halted. A single mission was sufficient to replenish it and the Divisions resumed their drive across the open steppe-land.

On 23 August Panzer Group 1 forced a crossing of the Olym downstream from Guderian, and in the area of Kastornoye the point units of 1st and 2nd Groups met. Later that afternoon the main force of both groups linked up and a solid wall of armor extended from Gubkin to Yelets. Kleist Group moved out immediately to capture Voronezh but that city was not to be taken by coup-de-main. It was a regional capital with half a million citizens, most of whom worked in its giant arms factories. As in the case of Mtsensk, Stavka ordered Voronezh to be held at all costs, intending that Mtsensk be the northern and Voronezh the southern jaw of a Soviet pincer. Those two jaws would be massively reinforced and, when the Red Army opened it offensive, they would trap the Panzer Army Group and destroy it.

Hoepner Struggles to Reach Guderian’s Gap

Hoepner’s Panzer Group 4 had been so heavily engaged in the encirclement operations at Smolensk and in the continuing fighting around Vyasma that it could only withdraw individual Panzer Regiments from the battle line. Acting upon Kesselring’s orders these marched southwards to gain contact with Guderian now driving hard for Yelets.

On the Mtsensk sector Vietinghoff grouped his XXXXVI Panzer Corps in support of Second Infantry Army which was fighting desperately against the heavily reinforced Fiftieth Red Army. Stalin had ordered that Soviet formation in order to hold Mtsensk and Tula and form the northern pincer of Stavka’s planned counteroffensive. When Stumme’s XXXX Corps reached Vietinghoff he handed over the task of supporting Second Army and struck eastwards across the Neruts river, passed south of Khomotovo and halted at Krasnaya Zara where he positioned his Corps on Guderian’s left flank. Detained by the Vyasma battles and slowed by mud, neither Stumme’s XXXX nor Kuntzen’s LVII Panzer Corps had gained touch with Vietinghoff by the evening of 23 August, but late that night, to the west of Guderian’s Gap, the first elements of both Corps reached their concentration areas.

24 August, Vietinghoff swung towards Yefremov where his advance struck and dispersed the Twenty-first and Thirty-eighth Red Armies, both reinforced by workers’ battalions armed with Molotov cocktails and other primitive anti-tank devices.

Hoth Reaches Guderian’s Gap

Like Hoepner’s Group, Hoth’s Group 3 disengaged piecemeal from the Vyasma operation, then concentrated and began to march southwards, en route to “Guderian’s Gap.”

Through the end of August, Hoth drove his Group forward at top speed. Kesselring’s dispositions for the advance of Panzer Army Group to Gorki had long been redundant, but a rearrangement brought Panzer Groups 2 and 3 shoulder to shoulder forming the assault wave with 4 and 1 preparing to line the eastern and western salient walls respectively.

On the evening of 23 August Hoth’s Group gained touch with the others and halted at the junction of the Sosna and Don rivers with Hoepner’s Group on one flank and Guderian’s on the other. “Our pioneers worked all night bridging those rivers,” said Panzer Captain Wolfgang Hentschel, “so that the advance could press ahead.”

Panzer Army Group Drives on Gorki

Early in the morning of 25 August, Kesselring, set up his Field Headquarters in Yelets and coordinated the great wheeling movement which would bring the Panzer Groups in line abreast ready to advance towards Gorki, some 650km distant. WOTAN was behind schedule and it worried him, for every day’s delay served the enemy’s purpose. When his subordinates demanded time to rest their men and to service their vehicles he could give them only three days. WOTAN’s third phase had to open on 27 August. Military Intelligence had indicated that the Soviets were about to carry out a major withdrawal and Panzer Army Group had to be ready to exploit any weakness shown by the Red Army during that retreat.

The series of battles leading up to Gorki created a period of bitter fighting, of relentless attack and desperate defense. Weeks in which the sable candles of smoke rising in the still summer air marked the pyres of burning tanks. In essence, the course of operations from 27 August to the middle of September was characterized by the Soviets being confined to the towns along the salient walls from which they mounted furious attacks against the panzer formations ranging across the open countryside and destroying such opposition as they met. In its advance from Yefremov via Dankov to Skopin, Panzer Group 1 was so fiercely attacked by Red forces striking out of Novmoskovsk, that Guderian was compelled to detach Geyr’s XXIV Corps to support Kleist until an infantry Corps reached the area. A similar action was fought at Ryazan against an even heavier offensive, supported by troops of the Moscow Front, switched on internal lines from west to the east flank. Panzer Group 1 was fortunate in being aided by nature on the Ryazan sector. The river Ramova was not a single stream but a mass of riverlets running through marshland-a perfect barrier against Soviet armor striking from the west and from the northwest. Kleist needed only to patrol on his side of the river and concentrated the bulk of his force on the high ground between the Ramova and the Raga, the latter river forming the boundary between Panzer Groups 1 and 2.

Guided by reconnaissance aircraft and supported by Stukas the panzer formations of each Group dealt with any crisis which arose on a neighbor’s flank. An analysis of Russian tank tactics highlights the difference between the Red Army’s highly skilled, pre-war crews and its more recently trained men. A post-battle report stated:

The enemy’s second attack (on the right flank) made good use of ground, coming up out of the shallow valley of the river and screened by the low hills on the eastern side of the road. This wave of machines got in amongst the artillery of 3rd Panzer Division which was limbering up ready to move forward. Hastily laid belts of mines and flame throwers drove back the T26s…The third attack was incompetently mounted and a whole tank battalion moved on the skyline across a

ridge. Our anti-tank guns picked the machines off and destroyed the whole unit…

Kesselring’s handling of his Army Group was masterly and he coolly detached units to bolster a threatened sector or created battle groups to strengthen a panzer attack. His energy and presence were an inspiration to his men.

Guderian’s Group, bypassing towns and crushing opposition, moved so fast that on 5 September, Kesselring was forced to halt it at Murom until Hoth and Hoepner had drawn level. The towns of Kylebaki and Vyksa fell to Panzer Group 3 on the following day and Hoth detached his LVI Panzer Corps to help take the strategic road and rail center of Arzhamas against the fanatic defense of a Shock Army specially created to hold it. With the full of Arzhamas on the 7th, the Soviet formations opposing Panzer Group 4 broke. As they fled Hoepner sent out his armored car battalions to patrol the west bank of the Volga, while 2nd and 10th Panzer Divisions went racing ahead to pursue the enemy and to gain ground. Wireless signals advised Hoepner that Bogorodsk had been taken, then that the advance guard had seized Kstovo and later that day had pushed on to the Volga. But Hoepner desperately needed infantry reinforcements and Kesselring sent in waves of Ju-52s, each carrying a Rifle Section. Within five hours two battalions of 258th Division had been flown in. The 5th and 11th Panzer Divisions of XXXXVI Corps moved fast to support Stumme’s XXXX Corps while LVII Corps continued with the unglamorous but vital task of strengthening the salient walls. By 10 September the Panzer Army Group was positioned ready to begin the final advance to Gorki. Group 1, on the left, had reached the Andreyevo sector and Guderian was advancing towards Gorki supported by Hoth’s Group 3. Meanwhile Hoepner’s Group 4 crossed the Volga against fanatical resistance and massive, all-arms counterattacks, and went on to establish bridgeheads on the river’s eastern bank.

On 12 and 13 September a vast air fleet, under Kesselring’s direct control, launched waves of raids upon Gorki. Stukas bombed Russian strongpoints and gun emplacements, until there was no fire from Soviet anti-aircraft batteries to defer the Heinkel squadrons which cruised across the sky bombing Gorki and the neighboring town of Dzerzinsk at will. The impotence of the Red Air Force is explained in a Luftwaffe report covering the period from the opening of WOTAN: “Soviet air operations were made initially on a mass scale but heavy losses reduced these to attacks by four or even fewer Stormovik aircraft on any one time…[they were] nuisance raids which had little effect…” The total number of enemy aircraft destroyed during the period was 2700 but the report does not state aircraft types: “…the Soviets could produce planes in abundance but not pilots sufficiently well trained to challenge our airmen…”

Resistance to the infantry patrols of 29th Division which entered both towns on the following day was weak and soon beaten down. Opposition on the eastern flank had been crushed and when Kleist Group secured Andreyevo, to the southeast of Vladimir the western sector was also firm. A German cordon, with both flanks secure, extended south of the Gorki-Vladimir-Moscow highway.

On 14 September Panzer Army Group Headquarters ordered a defensive posture for the following day in anticipation of massive Russian attacks. Those assaults came on the 15th and 16th, employing masses of infantry, tanks, and cavalry supported by artillery barrages of hitherto unknown intensity. Furious though those assaults were they were everywhere beaten back by German troops who knew they were winning: as one German major put it, “Thank Heaven for Ivan’s predictability. He attacks the same sector at precise intervals. Once his most recent assaults have been driven off we know things will be quiet until the stated interval has elapsed. When that new attack comes in we are ready for it. His tactics are almost routine. A very long preliminary barrage which ends abruptly. Then a short pause and the barrage resumes for five minutes. Under its cover his tanks roll forward and as they come close our panzer outpost line swings round and pretends to flee in panic. The Reds chase the ‘fleeing’ vehicles and are impaled on our anti-tank line…It never fails…”

But those days had been ones of deep crisis causing a signal to be sent to all units on the 17th for the defensive posture to be maintained throughout the following two days. Where possible, the time was to be spent in vehicle maintenance so that when the attack opened against Moscow, every possible panzer would be a “runner.”

Causes for Concern

On 9 September, the Field armies reported to OKH that losses from casualties and sickness were not being made good. Statistically, each German Infantry Division had lost the equivalent of a whole regiment and that scale of losses was also reflected in armored fighting vehicle strengths. When WOTAN opened only Panzer Group 4 had been at full establishment with Groups 1 and 3 at 70% and Panzer Group 2 at only 50%. To OKH the worrying question was whether Kesselring’s Army Group would be so drained of strength that it would be too weak to fulfill its mission. On the same day a memo from Foreign Armies (East) advised Hitler that the Red Army in the West had 200 front-line Infantry Divisions, 35 Cavalry Divisions, and 40 Tank Brigades, with another 63 Divisions in Finland, the Caucuses, and the Far East. That memorandum went on to warn that “…the Russian leaders are beginning to coordinate all arms very skillfully in their operations…” The warning was clear: WOTAN should be cancelled. Hitler ignored that warning. The operation would continue.

The second week of September was highlighted for the infantry and panzer forces around Mtsensk and Voronezh by a series of major Red Army offensives.

The Intelligence Section summary of 20 September reported, “The Siberian troops first encountered (on 15 September) maintained their attacks until yesterday morning. These attacks were bravely made but badly led. Prisoners stated that they had been foot marching for six weeks…There are 36 Divisions still in the Far East preparing to move westwards…”

Supreme Stavka, in desperation, were dredging the depths to stave off German conquest and launching major offensives with their reserves. Those at Mtsensk and Voronezh, made to close “Guderian’s Gap,” were the major ones. Whole Divisions of NKVD troops were concentrated in both areas and swung into action with such élan that their initial attacks forced the German infantry to retreat. But Stavka had made two errors. Firstly, so great a concentration of men in the cramped Mtsensk appendix restricted the armored formations, and secondly, although at Voronezh there was room for maneuver the garrison was equipped with only undergunned, light, T26 tanks. The fighting at both places was bitter and both sides knew that its outcome would depend upon which of them broke first. It was the Soviets, bombed from the air, pounded by artillery, and facing the fire of German soldiers fighting for their lives, whose morale cracked. Although the NKVD still marched into machine gun fire as unwaveringly as the Siberians or the cadets of the Voronezh military academies, the German troops sensed that the enemy’s spirit was gone. General Lothar Rendulic, commanding 52nd Infantry Division, wrote “Stavka recognized…that the standard Russian infantryman’s offensive quality was poor and that he needed the prop of overwhelming artillery and armor.” In the Mtsensk and Voronezh battles the Red Army’s armor and air support was eroded, and without those buttresses the Soviet infantry lost heart and were slaughtered. This paradox-initial fanatical struggles followed by a sudden and total collapse-was a feature encountered during the subsequent stages of WOTAN. The failure of the NKVD and the Siberians to crush the Germans affected the morale of the ordinary Red Army units encountered by the Panzer Army Group.

The presence of the Siberians on the battlefield was countered politically. Messages between Berlin and Tokyo were followed by belligerent, anti-Soviet editorials in semi-official Japanese newspapers. These alarmed the Kremlin, which halted abruptly the flow of Siberian Divisions to the west, for these might be needed to fight in Manchuria. The surge of reinforcements from the central regions of the Soviet Union also slowed as Panzer Army Group’s advances and Luftwaffe air raids cut railway lines forcing the Red Infantry to undertake wearisome foot marches to the battle front.

The Westward Advance to Capture Moscow

On 19 September, Sovinformbureau announced “The battle for Moscow has resumed with attacks…by the fascist Army Group von Bock…Waves of enemy troops made one assault after another…” On the same day OKH also reported that Maloarchangelsk had been captured without resistance and that German formations were within 7km of Aleksin. It concluded “Weak enemy attacks indicate that the Red Army’s resistance is beginning to crumble…”

Concurrent with the opening of Army Group Center’s offensive against Moscow, the leading elements of Panzer Army Group having spent two days regrouping and replenishing, began their westward drive. Hoepner created a strong battle group from units lining the salient’s eastern wall and sent it out to gain the area between Kstovo and Balaxna. Battle group Schirmer not only enlarged the bridgeheads on the Volga’s eastern bank but also cut the main east-west railway line.

While Panzer Groups 2 and 3 completed their regrouping, Panzer Group 1, echeloned along the salient’s western wall, was defending itself tenaciously against the Red Army’s fanatical assaults. Pioneer detachments working at top speed repaired the railway line between Michurinsk and Murom so that Infantry Divisions could be “lifted” by train to release the panzer formations for more active duties; and one Corps of Kleist’s Panzer Group promptly struck and seized Krasni Mayek to protect Panzer Army Group’s southern flank.

On 19 September, under a lowering sky, Panzer Group 2 on the right of Moscow highway and Panzer Group 3 on left, moved from Gorokovyets to open WOTAN’s final phase. The number of “runners” with each Group had sunk considerably in the bitter fighting but the Field workshops had repaired damaged vehicles and had cannibalized those too badly wrecked to repair. The first waves of Panzer Group 2 disposed 200 machines and Group 3 nearly 240. Throughout the two days of inactivity relays of transport aircraft brought in only shells and fuel. With petrol tanks filled to the brim and covered by a rolling barrage the two Groups advanced side by side westward towards Moscow. At midday the September gloom vanished to be replaced by cloudless blue skies. The Stukas which had been grounded reentered the battle, taking off from advanced airfields outside Murom, Kylebaki, and Vyksa. Opposition to the German advance, light to begin with, grew despite the dive bomber raids, and the combined forces of XXIV and XXXXVII Panzer Corps were able to advance only slowly on the northern side of the highway. The two Corps of Panzer Group 1 made better progress along the southern flank bouncing across marshland.

Panzer Group 4’s war diary entry of 21 September records that 2ns Panzer Division (XXXX Corps) was attacked south of Kstovo by what was estimated to be a whole Division of Cavalry. The horsemen’s assaults to break through the Group’s front were crushed with almost total loss, but that series of charges had unnerved many German soldiers who saw with horror wounded horses galloping across the battlefield screaming in pain. Shrapnel had disemboweled others who dragged their entrails leaving swathes of blood in their wake.

Panzer Group 1 reported minimal opposition on 24 September, not the furious assaults out of Vladimir and Sudogda that had been anticipated. 1st Group’s right-wing Corps, amalgamated with the left-wing Corps of Panzer Group 3, attacked and gained ground quickly. The frontline soldiers realized that the weak opposition they were meeting indicated that the Red Army was all but defeated. One of these soldiers, Sergeant Strauch, said “24 September. We found the bodies of a number of their Commissars, all shot at point-blank range. If the Party isn’t executing them then the rank and file are…”

The recce battalions of Groups 2 and 3 approaching Vladimir met the phenomenon of large, organized bodies of Red Army troops standing, lining the roads, waiting to surrender. The officer commanding one group told General Geyr von Schweppenburg, who was riding with the recce point detachment, that revolution had broken out in Moscow, the government had been overthrown and its leaders shot. Von Bock’s soldiers were already in the capital’s inner suburbs. A flurry of signal messages confirmed the story. General Vlassov, a former dedicated communist, whose Twentieth Army had up to now staunchly defended the northwestern approaches to Moscow, was leading a military junta which had sued for peace terms.

“Our battalion and two others were ordered from the armored personnel carriers and into passenger trains. Russian officers, many with Tsarist cockades, escorted us…After several hours we reached Moscow’s West Station and marched to the city center. Units of Bock’s Army Group were already there and in Red Square an SS detachment was blowing up Lenin’s tomb. At dusk massed searchlights lit up the flag staff over the Kremlin and deeply moved we saw the German War Standard flying at the mast head…”

The war in Russia was over. Now there would be a period of tidying up, politically, socially, and economically. The population had to be fed, the Red Army demobilized, and Russia incorporated into the Reich’s New Order. Hitler was triumphant. His battle plan Operation Wotan had won the war on the Eastern Front.

SOURCE: Reich Historical Archives

Labels:

alternate history,

germany,

hitler,

japan,

moscow,

nazis,

nkvd,

operation barbarossa,

soviet union,

stalin,

wotan,

wwii

Operation Barbarossa - Middle Phase (May 12, 1940 - August 7, 1940)

On May 12th, Hitler finally gave the go-ahead for the Panzers to resume their drive east after the infantry divisions had caught up. The ultimate objective of Army Group Center was the city of Smolensk, which commanded the road to Moscow. Facing the Germans was an old Soviet defensive line held by six armies. On May 15th, the Soviets launched an attack with 700 tanks against the 3rd Panzer Army. The Germans defeated this counterattack using their overwhelming air superiority. The 2nd Panzer Army crossed the River Dnieper and closed on Smolensk from the south while the 3rd Panzer Army, after defeating the Soviet counter attack, closed in Smolensk from the north. Trapped between their pincers were three Soviet armies. On June 4th, the Panzer Groups closed the gap and 180,000 Red Army troops were captured.

On May 12th, Hitler finally gave the go-ahead for the Panzers to resume their drive east after the infantry divisions had caught up. The ultimate objective of Army Group Center was the city of Smolensk, which commanded the road to Moscow. Facing the Germans was an old Soviet defensive line held by six armies. On May 15th, the Soviets launched an attack with 700 tanks against the 3rd Panzer Army. The Germans defeated this counterattack using their overwhelming air superiority. The 2nd Panzer Army crossed the River Dnieper and closed on Smolensk from the south while the 3rd Panzer Army, after defeating the Soviet counter attack, closed in Smolensk from the north. Trapped between their pincers were three Soviet armies. On June 4th, the Panzer Groups closed the gap and 180,000 Red Army troops were captured.Four weeks into the campaign, the Germans realized they had grossly underestimated the strength of the Soviets. The German troops had run out of their initial supplies but still had not attained the expected strategic freedom of movement. Operations were now slowed down to allow for a resupply; the delay was to be used to adapt the strategy to the new situation. Hitler had lost faith in battles of encirclement as large numbers of Soviet soldiers had continued to escape them and now believed he could defeat the Soviets by inflicting severe economic damage, depriving them from the industrial capacity to continue the war. That meant the seizure of the industrial center of Charkov, the Donets Basin and the oil fields of the Caucasus in the south and a speedy capture of Leningrad, a major center of military production, in the north. Hitler then issued an order to send Army Group Center's tanks to the north and south, temporarily halting the drive to Moscow.

The German generals vehemently opposed the plan as the bulk of the Red Army was deployed near Moscow and an attack there would have a chance of winning the war — also because it was a crucial railway center — but Hitler was adamant and the tanks were diverted. By late-May below the Pinsk Marshes, the Germans had come within a few miles of Kiev. The 1st Panzer Army then went south while the German 17th Army struck east and in between the Germans trapped three Soviet armies near Uman. As the Germans eliminated the pocket, the tanks turned north and crossed the Dnieper. Meanwhile, the 2nd Panzer Army, diverted from Army Group Center, had crossed the River Desna with 2nd Army on its right flank. The two Panzer armies now trapped four Soviet armies and parts of two others.

For its final attack on Leningrad, the 4th Panzer Army was reinforced by tanks from Army Group Center. On June 17th, the Panzers broke through the Soviet defenses and the German 16th Army attacked to the northeast, the 18th Army cleared Estonia and advanced to Lake Peipus. By the beginning of July, 4th Panzer Army had penetrated to within 30 miles (50 km) of Leningrad. The Finns had pushed southeast on both sides of Lake Ladoga reaching the old Finnish-Soviet frontier.

At this stage Hitler ordered the final destruction of Leningrad with no prisoners taken, and on July 19th, Army Group North began the final push which within ten days brought it within seven miles (11 km) of the city. However the pace of advance over the last ten kilometers proved very slow and the casualties mounted. At this stage Hitler lost patience and ordered that Leningrad should not be stormed but starved into submission. He needed the tanks of Army Group North transferred to Army Group Center for an all-out drive to Moscow.

Before the attack on Moscow could begin, operations in Kiev needed to be finished. Half of Army Group Center had swung to the south in the back of the Kiev position, while Army Group South moved to the north from its Dniepr bridgehead. The encirclement of Soviet Forces in Kiev was achieved on July 27th. The encircled Soviets did not give up easily, and a savage battle ensued in which the Soviets were hammered with tanks, artillery and aerial bombardment. In the end, after ten days of vicious fighting, the Germans claimed over 600,000 Soviet soldiers captured but that was false, the German did capture 600,000 males between the ages of 15-70 but only 480,000 were soldiers out of which 180,000 broke out netting the Axis 300,000 Prisoners of war.

Before the attack on Moscow could begin, operations in Kiev needed to be finished. Half of Army Group Center had swung to the south in the back of the Kiev position, while Army Group South moved to the north from its Dniepr bridgehead. The encirclement of Soviet Forces in Kiev was achieved on July 27th. The encircled Soviets did not give up easily, and a savage battle ensued in which the Soviets were hammered with tanks, artillery and aerial bombardment. In the end, after ten days of vicious fighting, the Germans claimed over 600,000 Soviet soldiers captured but that was false, the German did capture 600,000 males between the ages of 15-70 but only 480,000 were soldiers out of which 180,000 broke out netting the Axis 300,000 Prisoners of war.SOURCE: Reich Historical Archives

Labels:

alternate history,

germany,

hitler,

nazis,

operation barbarossa,

soviet union,

wwii

Operation Barbarossa - Opening Phase (May 1, 1940 - May 12, 1940)

At 3:15 am on May 1, 1940, the Axis attacked. It is difficult to precisely pinpoint the strength of the opposing sides in this initial phase, as most German figures include reserves slated for the East but not yet committed, as well as several other issues of comparability between the German and USSR's figures. A reasonable estimate is that roughly three million Wehrmacht troops went into action on 1 May, and that they were facing slightly fewer Soviet troops in the border Military Districts. The contribution of the German allies would generally only begin to make itself felt later in the campaign. The surprise was complete: Stavka, alarmed by reports that Wehrmacht units approached the border in battle deployment, had at 00:30 AM ordered to warn the border troops that war was imminent, only a small number of units were alerted in time.

At 3:15 am on May 1, 1940, the Axis attacked. It is difficult to precisely pinpoint the strength of the opposing sides in this initial phase, as most German figures include reserves slated for the East but not yet committed, as well as several other issues of comparability between the German and USSR's figures. A reasonable estimate is that roughly three million Wehrmacht troops went into action on 1 May, and that they were facing slightly fewer Soviet troops in the border Military Districts. The contribution of the German allies would generally only begin to make itself felt later in the campaign. The surprise was complete: Stavka, alarmed by reports that Wehrmacht units approached the border in battle deployment, had at 00:30 AM ordered to warn the border troops that war was imminent, only a small number of units were alerted in time. The shock stemmed less from the timing of the attack than from the sheer number of Axis troops who struck into Soviet territory simultaneously. Aside from the roughly 3.2 million German land forces engaged in, or earmarked for the Eastern Campaign, about 500,000 Romanian, Hungarian, Slovakian and Italian troops eventually accompanied the German forces, while the Army of Finland made a major contribution in the north. The 250th Spanish "Blue" Infantry Division was an odd unit, representing neither an Axis or a Waffen-SS volunteer formation, but that of Spanish Nazis and sympathisers.